29 Jul MEDICAID PHARMACY CARVE-OUTS

Wisconsin Pharmacy Carve-Out

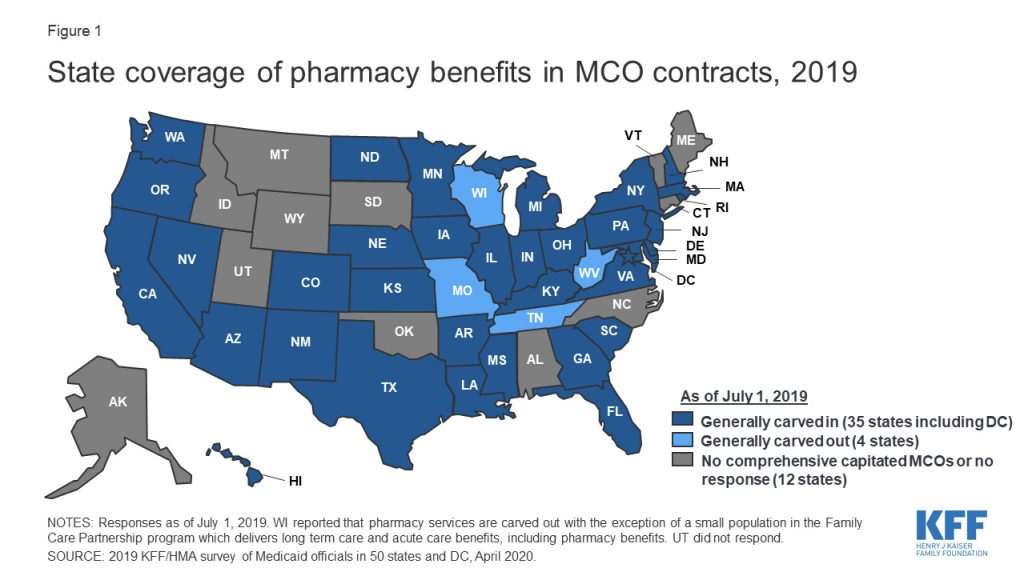

Last year, the Wisconsin Department of Health Services carved out prescription drugs from the Family Care Partnership Program and transitioned to a Fee-for-Service (FFS) delivery model. The carve-out ensured compliance with the 2020 Medicaid and CHIP Managed Care Final Rule and eliminated the need for Managed Care Organizations (MCOs) to implement their own drug utilization review program. In addition, Wisconsin believes that the carve-out will reduce Medicaid costs by lowering prescription drug prices. To date, Wisconsin, Tennessee, West Virginia, and Missouri have carved-out their Medicaid pharmacy benefits.

How States Manage Medicaid Prescription Drug Costs

Over time, Medicaid’s drug spend has skyrocketed, and in 2017 it reached $64 billion. While states are not required to include pharmacy benefits in their Medicaid programs, the majority do because it is a crucial part of modern medicine and improves the coordination of care. Due to Medicaid expansion, surges in enrollment, and the pandemic-driven recession, the problem has only been exacerbated. When states are facing fiscal pressure, they usually turn to different payment strategies, utilization controls, benefit delivery models, or reductions in program benefits to reduce costs.

Typically, states will utilize one of two different approaches to manage the costs of prescription drugs. The most common approach is for a state to contract with a MCO and PBM to manage their pharmacy benefits. The alternative is to carve-out pharmacy benefits and manage drugs through a fee-for-service delivery model. Below, we will review the pros and cons of each approach to understand their impact on Medicaid drug costs better.

ACA Reforms Drug Rebate Policies

States who opt to carve-out Medicaid prescription drug benefits believe they will receive lower drug prices by negotiating with pharmaceutical manufacturers directly. This approach has been successful in some situations; however, the passage of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) introduced drug rebate policy changes that completely altered state prescription drug plans.

Under the ACA, drug manufacturers were required to increase the rebate percentage for states from 15.1 percent to 23.1 percent. In addition to the eight-point increase, MCO beneficiaries were also made eligible for these rebates. Prior to the ACA, these rebates were only for enrollees in fee-for-service Medicaid programs.

After the ACA was implemented, The Lewin Group, a premier national health care and human services consulting firm, examined the impact of these changes. Their report, Projected Impacts of Adopting a Pharmacy Carve-In Approach Within Medicaid Capitation Programs, revealed that the ACA eliminated the savings advantage that cave-outs previously had. In addition, their report studied carve-outs in fourteen states and concluded that those states could save $12 billion over a ten-year period by carving-in pharmacy benefits.

Following the ACA’s rebate and eligibility changes, the majority of states contracted with MCOs to deliver care to Medicaid beneficiaries. By 2017, there were 39 states with Medicaid MCO contracts, and 35 had carved-in their Medicaid prescription drug benefits. As of July 2018, 40 states were contracted with risk-based managed care plans, and 5 had carved out prescription drugs.

Carve-Outs and Other Efforts to Reduce Drug Costs

While most states have kept pharmacy benefits carved into their managed care contracts, there continues to be carve-out activity and other efforts to reduce costs.

New York was scheduled to carve out pharmacy benefits beginning April 1, 2021. Medicaid members enrolled in managed care plans, health and recovery plans, and HIV-special needs plans would begin to receive their prescriptions through a Medicaid FFS pharmacy program instead of their MCO. However, the transition has been delayed two years due to an amendment of the state budget after lobbying efforts. The transition to the new Medicaid FFS model will now go into effect on April 1, 2023.

In 2019, Ohio’s legislature mandated the state to select a Single Pharmacy Benefit Manager (SPBM) after growing criticism of how its pharmacy benefits were being managed. Following the order, the state issued a RFP for a SPBM that would contract with Ohio directly to improve transparency and manage its prescription drug program. Ohio’s newly designed program is expected to launch at the beginning of 2022.

In 2019, Governor Gavin Newsom signed an executive order that California would move all pharmacy services for Medi-Cal to a FFS model. As a result, California expects to negotiate better drug prices from manufactures by consolidating purchasing power and leveraging the state’s population size. According to the Legislative Analyst’s Office, carving-out could result in hundreds of millions in savings annually. However, the move is controversial. There are concerns over its potential impact on MCOs, PBMs, pharmacies and the coordination of care since California’s Medicaid pharmacy benefit is currently administered by ten separate PBMs responsible for 90% of the state’s Medicaid beneficiaries.

In 2019, Michigan’s Department of Health and Human Services issued a notice of proposed policy announcing that outpatient prescription drug coverage would no longer be a benefit and the state would transition to a FFS model. The state anticipated saving around $10 million annually through drug rebates and eliminating related administrative capitation costs. Critics opposing the decision claimed that it did not align with MHP’s goal of delivering whole-person integrated care. They believed that out-of-pocket costs would increase and members would not have the appropriate overview of their prescriptions. After considering the carve-out, the state decided to implement a single Medicaid Preferred Drug List (PDL) instead.

Like Michigan, Washington state has also implemented a PDL to reduce costs. The Apple Health Preferred Drug List was introduced in 2018, and all Medicaid MCO plans and fee-for-service plans were required to use the PDL.

Medicaid Payers and PBMs

While states decide what delivery model they use to coordinate care, MCOs support carving-in Medicaid prescription drug benefits. Whenever a program benefit, such as prescription drugs, is carved out it makes the coordination of care difficult and awkward. MCOs believe that when pharmacy benefits are carved-in, Medicaid program performance is strengthened, quality is improved, and costs are reduced.

In 2015, America’s Health Insurance Plans (AHIP) commissioned a report from The Menges Group that analyzed the impact of carving-out prescription drug benefits from MCO benefit packages. According to the report, “the decision to carve out pharmacy benefits is likely to significantly increase costs for states and the Federal government”. The analysis also discovered that in “28 states using the carve-in model, the net cost per prescription was 14.6 percent lower than the average net cost per prescription in states not carving in pharmacy.”

Critics of the managed care model argue that PBMs contribute to the high cost of drugs, as they function like middlemen in getting drugs from manufacturers to patients. PBMs obviously disagree with this criticism. Instead, they argue that they are uniquely positioned to help manage the cost of Medicaid pharmacy benefits. PBMs work to negotiate rebates, manage formularies, provide mail-order options to patients, manage the distribution of drugs among pharmacies, and provide specialty drug services.

Over time pharmacy spend has become a growing expenditure in state budgets. As a result of increased fiscal pressure states are exploring different delivery models, PDLs, and legislation to reduce prescription drug costs. While most states deliver pharmacy benefits through managed care models, a handful have chosen to carve-out prescription drugs and transition to FFS models. In addition to lowering drug costs, states should also look for cost avoidance opportunities and further efficiency in their Medicaid plans to reduce costs.